Technical Proof on Staged Accidents

International conference paper from the Institute of Traffic Accident Investigators, London

author: Michael Weber (Copyright) published 1999

Abstract

The RTA expert can assist in the uncovering of staged or faked vehicular accidents. Prime categories of fraudulent claims and their motives are enumerated. The methods of technical proof are expounded, followed by practical hints on useful tools and techniques. Examples depict the theoretical concepts.

Introduction

Over the last few decades insurance companies in Germany, Switzerland and Austria have noted a significant rise in fraudulent claims. There are several reasons for this phenomenon. One of them certainly is that the normal citizen is not conscious of any guilt when defrauding the anonymous insurance company, and also that the risk taken by doing so is very low. Should a fraudulent claim be uncovered, even the public prosecution system seems to consider it to be a fairly trivial offence.

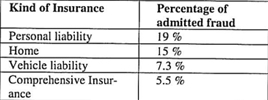

The growth in insurance fraud is depicted by table 1, published by the GfK (Assoc. for research on consumer behaviour). The data presented is based on in-depth interviews with anonymous consumers. One of the questions posed was whether they had defrauded their insurance company during the last five years.

In the following report we shall limit ourselves to vehicular fraud. Conservative estimates suggest an annual financial loss of two billion euros, solely as a result of defrauding vehicle insurance companies. Trying to reduce their costs, the insurance companies have begun to exhibit a rising tendency to combat fraudulent claims. When suspecting a bogus accident, they refuse regulation of claims. In numerous cases this behaviour will result in a civil proceeding. In most cases, the litigant parties will call for expert witness(es). The judge will then appoint an independent technical expert to investigate the case.

Motives for Faked Accidents

In most countries the repair (or replacement) of the damaged vehicle is supervised by the insurance company. In contrast to this, in Germany, Switzerland and Austria, the ‘victim’ of an accident may legally demand the money for repairs without any legal duty to actually repair his/her vehicle. The repair costs are calculated by a technical expert hired by the victim, or even by a garage proprietor. The German expression denoting this procedure may be translated as „virtual liquidation“.

Obviously, the claimant could not take any advantage of this situation when leaving an impeccable vehicle to a thorough repair. By conducting an incomplete repair, the fitting of used parts, going to a scrapyard (garage), up to 8 of ordinary repair costs can be saved (legally!).

Kind of Insurance – Percentage of admitted fraud

Personal liability: 19 %

Home: 15 %

Vehicle liability: 7.3 %

Comprehensive Insurance: 5.5 %

Fig. 1: GFK-study

For this reason a great many criminals organise faked accidents, mostly involving expensive cars. As long as the insurance company of the ‘guilty driver’ is changed each time, there is very little risk of being detected. In large towns especially, organised gangs carrying out this work and with up to 100 people have been uncovered. Additional possibilities for gain are offered by the use of pre-damaged or insufficiently repaired cars.

But also normal citizens profit from insurance fraud without any consciousness of guilt. In order to get money after a damage of their own fault, it is quite common to ‘adapt’ the accident report according to their own purposes.

Prime Categories of Faked Accidents

The Planned Accident

According to this first modus operandi the accident actually takes place. It is planned and conducted by all participants. In many cases, the incident is given the official touch by actually calling the police in order to get a report on it. In these cases the accident has been conducted in situ. When there is no official report on the accident, the accident is often carried out on private properties and „shifted“ to public areas for the insurance report.

The Provoked Accident

In this case we have a perpetrator and a victim.

The perpetrator plans and executes the accident on his own, while the victim is unconscious of what is taking place. The scenario is always chosen such that the prima facie proof is on the side of the culprit. Common forms are:

- provoked rear-ender

- The victim is surprised by sudden and harsh braking of the car in front. After the accident the culprit has a plausible excuse for his breaking manoeuvre, such as a pedestrian entering the roadway or a traffic light changing to amber. Even if the safety distance of the follower is sufficient, success may be guaranteed by switching off the brake lights. With most cars it suffices to switch off the ignition prior to braking.

- right-of-way trap

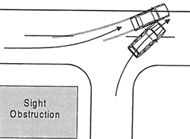

- Confronted with an every-day situation where he has the right of way, the culprit refrains from any defensive action. Instead of braking or swerving he accelerates and often steers towards his victim’s car. Fig 2 depicts an example of an accident that was obviously provoked.

- blind corner shooting

- The culprit chooses a location where non-local drivers are often forced to a sudden lane-change manoeuvre. Hiding his car in the blind spot of his victim’s outer mirror, the culprit accelerates as soon as the lane change of the victim is initiated. After being side-swiped by the victim, the culprit stops instantly to prove his lateral position and therefore the lane change of his victim.

The Exploited Accident

After an occasional accident, the favoured driver tries to get a higher compensation than justified. He either does not reveal pre-existing damages or enlarges the original damages produced by the accident. The second possibility only makes sense in virtual liquidation cases.

(Fig. 2: Right of way trap)

The „hunter“ takes advantage of the sight obstruction. The surprisingly fast reaction of his prey tempts him to pursuit into the opposite lane.

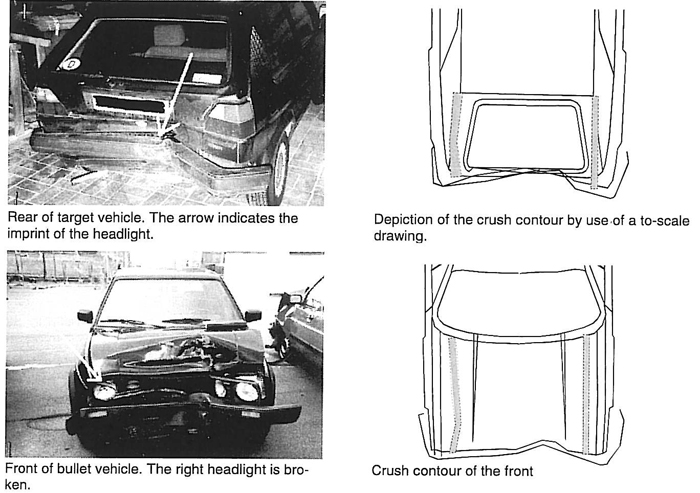

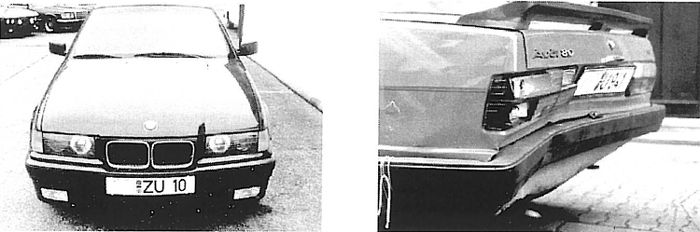

Fig. 3.:Deduction of the crush contour using photographs

The Fictitious Accident

The accident reported to the insurance company never actually happened. The cars involved have never been in contact. The damages are either produced manually or stem from a former accident.

Ways of Technical Proof

In general, the analysis should be conducted in two steps. First of all we should check if there is a correspondence between the damage patterns of the vehicles involved. If there is, one should then check the plausibility of the unfolding of the accident as reported by the participants (and witnesses). The conducting of this second step can be based on the results of the compatibility analysis, such as mutual orientation, brake diving and impact closing speed. In most cases the analysis has to be based on damage photographs.

Compatibility

The common approach consists of four consecutive steps

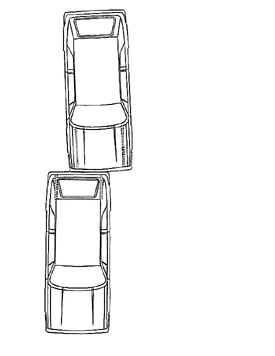

- Morphology – Three-dimensional mapping of the shape and extent of the damage, using photographs, reference to scaled drawings as depicted in fig 3 or measurements taken from the same make and model.

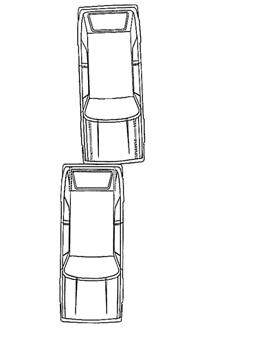

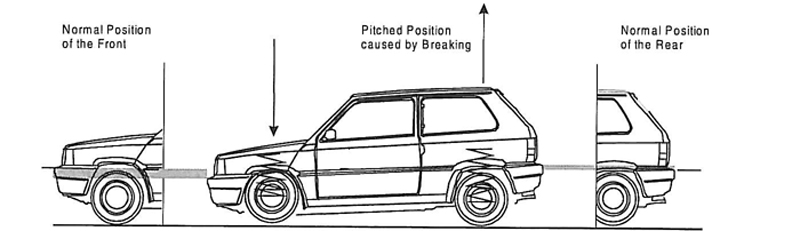

- Mutual Orientation – Photographs must be scanned for unambiguous damage patterns in order to fix the impact constellation: offset, impact angle and vertical assignment. For example, the circular imprint on the rear bumper of the target vehicle in fig 3 corresponds to the headlight of the bullet vehicle leading to the impact constellation depicted in fig 4: 20 % offset, in-line collision and nose diving prior to impact.

- Detailed Analysis – Based on the mutual orientation established in the previous step, every detail of the impact pattern may now be checked. Every imprint has to have a counterpart in the corresponding position. The morphology of the contact zones must coincide, as illustrated by fig 5.

- Damage Extent Comparison – A common pitfall – especially if not conducted as the last step- because the rigidity of the body structures involved often differ significantly, compare fig 6. Also the rigidity of structural members may be severely direction dependent

Plausibility

Even if the damages to the cars involved coincide, the accident may still be faked. As has been said with respect to virtual liquidation, it is possible to make money even when damaging an intact car. When damaging fairly new cars, the defrauders take care to produce only superficial dents in order to ease the repair, while charging for new replacement parts.

Any accident is – by definition – the result of an occasional event. The claimant must thus prove that the damages were produced accidentally, and it is no easy matter to simulate an occasional event by intentional driving manoeuvres. The most common errors:

1. Absence of Defensive Action – Although the circumstances give evidence for sufficient time for defensive action, there are no signs of braking or swerving. The most obvious indicator surely is the lack of skid marks (for non-ABS cars). In order to detect a braking manoeuvre, the respective heights of the impact prints may be compared. Nose diving will lead to a correspondence deviation from the curb weight positions of about 8 cm at full deceleration. An example for nose-diving is given in fig 6.

(Fig. 4)

(Fig. 5)

(Fig. 6)

2. Doubtful Coordination of Driving Manoeuvres

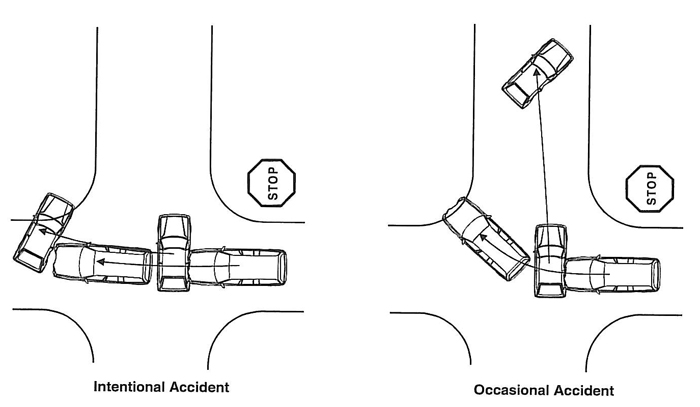

- Regarding occasional accidents, the most common situation is that both vehicles are in motion until impact. When simulating the incident this may only be achieved with in-line traffic, ie, rear-ender, side-scraping, push-off against guard rail, etc. The more the moving directions approach the perpendicular, the more difficult it becomes to coordinate the driving manoeuvres. It is nearly impossible to simulate a side-swipe with a car darting out of a subordinate road. One characteristic of bogus accidents that correspond to the above description is that the car in priority will always be motionless at impact, as can easily be deduced from the spin-out trajectories and the damage patterns.

3. Evidence of Intention

- When a parked car is hit intentionally, the collision angle derived from the damage patterns is often extraordinarily large. In provoked accidents, the hunter often chases his prey up to uncommon points of impact.

(Fig. 8 – image not available at the moment)

Fig 8 depicts the difference between the occasional and intentional side-swipe at a crossing. In the real accident the driver in priority has no time to reduce his speed prior to impact. The residual speed after impact will result in extended post-crash motion. In contrast, the stationary car in the faked accident will exhibit exclusively lateral motion.

(Fig. 7)

Simulated Injuries

In order to receive compensation for personal damage, defrauders often claim personal injuries after an accident. He/she is restricted to such injuries that cannot be objectively ascertained by medical examination, in general soft-tissue injuries. Very common examples are whiplash injuries after rear-end collisions.

The technical expert may calculate the biomechanical stress imposed on the occupants by the impact. Based on this data the medical expert may judge whether this stress is sufficient to produce the injury claimed. Interestingly enough, most whiplash injuries occur at delta v below 15 km/h. In Germany, more than half a billion Euros are paid each year for the compensation of 400,000 whiplash-cases.

Miscellaneous Methods of Fraud

In Germany, about 5 of the compensation paid out in private liability cases is for vehicular damages. The rate of fraudulent claims is very high in this sector. The general aim is to receive compensation for accidental damages that were otherwise not covered by insurance. But you get by with a little help from your friends (as you need someone to blame the damage on):

- Vandalism – Scratches produced by intentional vandalism are declared as the result of a bicycle side swipe.

- Capsized Motorcycles – Damages produced by sliding during a lay-down are declared as being the result of actions by a passing pedestrian.

- Own-fault accidents – Road run-offs, guard-rail contacts, minor parking contacts are explained by an alternative scenario, eg, evasive action made necessary due to a pedestrian darting out.

Often, the stories reported contradict physical laws, the morphology of the damages does not coincide with the object indicated as their source. The scenarios put forward as explanations for the damage incurred often diverge significantly from relevant common behavioural patterns.

Fig. 8: Comparative post – crash motion of a car in priority

Proof Techniques

To analyse geometric compatibility, you may choose one of the following techniques:

- super-imposing scale drawings of the objects involved in the accident under consideration, either on transparencies or by the use of CAD.

- super-imposing photographs of damage in photo-imaging software such as Corel PhotoPaint or Adobe Photoshop.

- reconstructing the impact situation using cars of same make and model

- covering a car of same make and model with transparent full-scale drawings of the damaging object as shown in fig 9.

In order to interpret the marks left – for instance for reading the direction of relative motion from the resulting scrape pattern – it is necessary to rely on test results. Common constellations are well documented in literature. Quite often, the solution is beyond the reach of scientific reasoning alone – only full-scale testing will produce firm evidence.

Real (occasional) accidents are also a valuable source of knowledge. It pays to build up a database of damage patterns produced by every-day accidents. This may provide answers to questions that otherwise could only be gained via crash-testing.

fig. 9: positioning of a full scale transparency

Conclusions

In Germany, technical experts play a pivotal role in the uncovering of faked RTAs. In numerous cases, common methods of criminological investigations fail, such that the technical proof may supply the only possible solution. Induced by a steady confrontation with bogus accidents, German experts have developed sophisticated investigative methods. So far, descriptions of these have only appeared in German-language publications, including many crash tests dedicated to this very field.

References

Papers:

- Die Aufklärung des KFZ-Versicherungsbetrugs – Pkw – Streifkollision Weber, M. Verkehrsunfall u. Fahrzeugtechnik 33

- Die Aufklärung des KFZ-Versicherungsbetrugs mittels technischer Beweisführung / Entwicklung einer Systematik zur Kompatibilitätsanalyse. Weber, M.: Schimmelpfennig, K.-H.: Verkehrsunfall und Fahrzeugtechnik 28 (1990)

- Die Zuordnung von Beschädigungszonen bei Berücksichtigung von Beladung, Verzögerung und Querbeschleunigung. Weber, M.: Dieling, W.: Verkehrsunfall und Fahrzeugtechnik 28 (1990)

- Die Aufklärung des Versicherungsbetruges bei zweidimensionalen Kollisionen. Weber, M.: Verkehrsunfall und Fahrzeugtechnik 30 (1992)

- Pkw-Serienkollisionen Weber, M.: Verkehrsunfall und Fahrzeugtechnik Jahrgang 34 (1996)

- Zur Belastung der Halswirbelsäule durch Auffahrunfälle Meyer, Hugemann, Weber: Verkehrsunfall und Fahrzeugtechnik 32 (1994)

- Freiwilligenversuche zum Halswirbelschleudertrauma bei Auffahrkollisionen, Meyer, Weber, Kalthoff, Castro, Schilgen: Verkehrsunfall und Fahrzeugtechnik Jahrgang 37 (1999)

- Do whiplash injuries occur in low speed rear impacts? – European Spine Society – The AcroMed Price for Spinal Research. Castro, Schilgen, Meyer, Weber, Peuker, Wörtler:Spine Number 6 1997

Books:

- Die Aufklärung des KFZ-Versicherungsbetruges – Grundlagen der Kompatibilitätsanalyse und Plausibilitätsprüfung. Weber, M. u.a. : 1. Auflage, Schriftenreihe Unfallrekonstruktion, Münster 1995 – ISBN 3-9804383-0-9.

- Whiplash injuries – Current concepts in prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of the cervical whisplash syndrome [edited by] Robert Gunzburg, Marck Szpalski, Lippincott-Raven Publishers

Drawings

All drawings created using VENUS DRAWING DATABASE.